|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. MIAMI HERALD Boxer Battles Guilt Stemming From Opponent's Death BY GREG COTE 26 February 2005

It has been one year now since Quiles killed his opponent. But it was not his fault, it was not a scandal, it was not a crime. It was boxing. They buried Luis Vallalta back in his native Peru. He was 34. Quiles, the same age, has been fighting ever since, but mostly out of the ring. Mostly himself. Bouts of guilt and remorse, depression and tortured sleep -- ''I cried a lot. I felt responsible.'' -- were fought with seclusion and binge drinking. He resented his sport for a long while, refusing to put on gloves again. He withdrew, not speaking publicly about the ordeal, the tragedy of two men, not one. ''I always felt lonely and hurt, but I'm starting to love myself,'' he says now on the anniversary of what changed him. ``This has got me closer to myself.'' This is a story about the brutal ballet, boxing, and about the journeymen pros who fight on the second tier, looking for a marquee, waiting for a payday. This is a story about getting past your nightmare. Trying to get your dream back. It happened Feb. 28, 2004, in a ring at a Seminole-run casino in Coconut Creek. Local card. No TV. Quiles (pronounced ''kwill-ess'') and Vallalta were fighting for the lightweight title of the North American Boxing Federation, a grade-B sanctioning body. The two men would split a modest $7,500 purse. Quiles won a close decision in a spirited bout that pleased the few hundred there. ''I hurt him really bad. I thought in round eight the referee would stop it, but the fight continued,'' Quiles recalled. After the last bell clanged, 'We gave each other a hug and kiss. I lifted his hands in the air and paraded him around the ring and gave him acknowledgement that he gave me a heck of a fight. We got a standing ovation. Once we parted ways he said gracias in Spanish. I said, `Thank you very much,' and we left.'' Boxers in many instances share a kinship that fosters mutual respect. ''A spiritual bond,'' Quiles said. ``When you fight another man, you share something. You feel him, you hold him.'' That respect is why Quiles is shocked to have heard more than once, on the street, others refer to the tragedy as if it had feathered his reputation. 'I have overheard, `This guy killed somebody!' Like they're glorifying that,'' he said, bitterly. ``That bothers me.'' Minutes after the fight, Vallalta would collapse in his dressing room, lapse into a coma and not regain consciousness. He died four days later at North Broward Medical Center of ''post-traumatic cerebral edema,'' or swelling of the brain. Vallalta's share of the purse would help pay to bury him. Warrior's Boxing Gym in Hollywood, where Quiles trains, helped defray the costs. There was no controversy attached to the tragedy. It was boxing. Even Vallalta's father absolved Quiles, saying he held ``no harsh feelings.'' Boxing deaths are rare, yet common enough to barely warrant headlines unless one of the fighters involved is a star. Ray ''Boom Boom'' Mancini accidentally causing the death of opponent Duk-Koo Kim in Las Vegas in 1982 was one of the most prominent examples of a boxing death, but dozens have died since. An American Medical Association analysis estimated there is roughly one death for every 7,700 boxing matches -- enough for the AMA to condemn the sport more than 20 years ago, in the wake of the Mancini fight. The AMA pulls no punches, stating that boxing's ``primary objective is to inflict injury.'' The fighters disagree. They see their ''sweet science'' as physical chess, requiring as much strategy and tactics as brawn. Like auto racers, boxers accept the assumption of risk -- even the ultimate risk. It is a ribbon of honor. Dale Earnhardt Jr. raced his No. 8 NASCAR Chevrolet just days after his famous father died from injuries suffered at Daytona International Speedway. So it was that Quiles' return to the ring, after five-plus months away -- after the mourning and the ''why me?'' and the hating his sport -- may have been inevitable. ''I don't know what to do with my life besides boxing,'' as he put it. His father and uncle were big fight fans. There was a speed bag in the basement and a boxing gym nearby as Quiles grew up in Lorraine, Ohio, the oldest of four kids, to parents born in Puerto Rico. ``My mother made me stop fighting at 13. But I knew it was what I wanted.'' Life was tough -- the story of so many who do this for a living. Quiles became a father at age 15, has been on his own since 16. His own father, an alcoholic, abandoned the family when Ricky was 8. The son followed the bad footsteps. ''Marijuana, cocaine and drinking, to be blunt about it,'' he said. In the mid-'90s he quit boxing for three years, ''and all I was doing was partying.'' He had to get away. He moved to Florida in abject desperation, knowing he had been letting his boxing talent slide, and knowing that was all he had. ''I should be dead or in prison,'' he said. ``Boxing was my lifeline.'' Despite the tragedy of a year ago -- perhaps because of it -- Quiles seems to have rediscovered his focus, his family, his dream. He has reconnected with his three kids, who live with their mother in Cleveland. He won his comeback fight this past August, a mental hurdle. ''I was scared, hoping [another tragedy] would not occur again,'' he said. ``It took a while to get back to feeling the love for the sport again.'' Another step came two months ago when he agreed to speak at a convention of the American Association of Professional Ringside Physicians, in Miami Beach. To that closed session of some 100, mostly doctors, he opened up for the first time. Dr. Charles Mandell, a Hollywood dentist, was there. ''I saw this whole purging,'' said Dr. Mandell. ``It was beyond eloquent. It was truthfulness. There wasn't one sound in that audience.'' Soon after, Quiles won his biggest fight yet, Feb. 4 at Hard Rock Casino in Hollywood, beating favored Edner Cherry in an International Boxing Federation bout televised by ESPN. It vaulted Quiles to No. 2 in the IBF lightweight rankings, to new stature and credibility as Quiles, improved his record to 37-6-3. Victory didn't come easily. 'He hit me so hard once in my right eardrum all I heard was, `Bzzzzzz,' '' Quiles said. ``He hit me so hard I saw five guys. I hit the one in the middle!'' He still works a regular job, serving food at a local Mexican restaurant, Tequila Ranch. But one or two more big wins and he may not be counting waiter tips anymore. Quiles trains most every day amid the echoes and humidity inside Warrior's Gym on U.S. 441, a store that sells dreams, and the men pushing him include new trainer Michael Moorer, the former heavyweight champion. The memory of Luis Vallalta motivates the boxer who survived. See, they were brothers, in a way. Two men the same age, both with kids, both fighting odds to make it big. The one who got lucky never stops thinking: It could have been me. ''He was in the same position I was,'' says Ricky Quiles, one year later. ``A good guy working hard.''

|

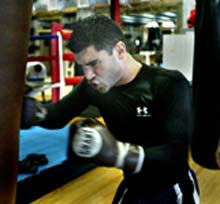

Ricky Quiles is in a small boxing gym in Hollywood, bouncing in the humidity, jabbing, sparring with shadows, fighting a ghost. The five-foot nine-inch, 135-pound lightweight is carrying another man on his back, in his mind. The other man may never go away.

Ricky Quiles is in a small boxing gym in Hollywood, bouncing in the humidity, jabbing, sparring with shadows, fighting a ghost. The five-foot nine-inch, 135-pound lightweight is carrying another man on his back, in his mind. The other man may never go away.