|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. The New York Times Keeping Symbol Standing is Challenging San Juan by ABBY GOODNOUGH July 11, 2004

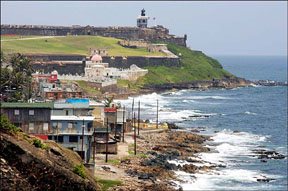

SAN JUAN, PR, July 8 -- La Muralla starts just past the cruise ship docks, hugging the touristy ruckus of Old San Juan and a traffic-choked street before it ends near the Capitol, facing the Atlantic. It is a cherished symbol of Puerto Rico, this thick, soaring wall that has endured for more than 400 years, but it is frailer than its bulk suggests. A 70-foot section of the wall crumbled one day in February, startling San Juan residents who thought it would last an eternity. Engineers and officials at the National Park Service, which tends the wall and two adjacent forts, blamed the constant rumble of trucks and buses along Calle Norzagaray, the street that abuts it. It was the largest piece of wall to collapse since 1938, when a much longer, higher section gave way to the pounding of waves from San Juan Bay. But in fact, chunks of La Muralla fall constantly, not only because of traffic but also because of pollution, poor repair work and the wet, salty air that is inescapable here. Now Old San Juan, the pastel-and-cobblestone neighborhood from which the larger city spread, is getting serious about preserving its 16th-century trademark, so iconic it is stamped on Puerto Rican license plates and many travel brochures.

"This wall is a symbol of our endurance," said Félix López, a cultural resources specialist for the park service's San Juan National Historic Site. "But it's very tricky. It looks very solid but there might be loose matter on the inside, or there might be a sidewalk on top of it. You've got to measure the cracks all the time." Spanish colonists started building La Muralla in the late 1500's, about a century after Christopher Columbus laid eyes on Puerto Rico in 1493. Construction continued over two centuries, with the final sections - including the one that recently tumbled - finished around 1785. The main materials were soft sandstone rubble and mortar, with a stucco exterior to protect the insides from water and wind. The final product is more than 3 miles long, up to 40 feet high and 45 feet thick.

It weathered five major attacks - by the British in 1595, 1598 and 1797, the Dutch in 1625 and the Americans in 1898 - and at least a few hurricanes. But while the Spanish did a fine job of maintaining the wall, the United States Army, which took over its care after seizing Puerto Rico in 1898, did not. Edwin Colón, the site's chief of maintenance for the last 25 years, said the Army had repeatedly patched the wall - including the part that fell in February - with concrete. That sealed in moisture and added weight, Mr. Colón said, hastening deterioration of the wall's innards. When the park service took over the wall and adjoining fortresses, El Morro and San Cristóbal, in 1963, it, too, replaced the stucco layer with concrete. Over the last six years, Mr. Colón has tried to recreate the stucco formula that the Spaniards used, a mix of sand, water and limestone. He runs a test kitchen of sorts near the west wall, a closet-size room lined with jars of sand from around Puerto Rico, which he adds to limestone and water to make a peanut-butter-like paste. He finally has what he considers the perfect mix, which he ages for at least six months before using it on the wall. "This is a lost art that is finally coming back," Mr. Colón said. "It's the best matter; it lasted 500 years."

Mr. Colón, who also searches Puerto Rico for replacement stones that resemble the originals, said it takes two years to teach masons the new, old way of repairing the wall. But the park cannot afford to hire any permanently, he said. A team of masons is also restoring several of the curvy sentry boxes that top the wall, though it has no plans to replace the 450 cannons that once stood on it, firing red-hot cannonballs on enemy galleons. The park has 1.2 million visitors a year, including passengers from cruise ships who stop in Old San Juan for the day. That figure does not include thousands who walk a footpath alongside the wall to where San Juan Bay meets the ocean. Nor does it count the masses who picnic, stroll or fly kites on the grassy knoll in front of El Morro, Old San Juan's version of Central Park's Sheep Meadow. "You know how the Statue of Liberty symbolizes everything important for the United States citizens?" Mr. López said. "Well, these forts and this wall are like that for us." Kite string gets caught in the wall, weeds spring from it, rats and pigeons inhabit it, and people scrawl graffiti across it. A few have even asked to rappel from the wall (the answer was no). "They do everything on it," said Walter Chávez, the park superintendent, who has enlisted young volunteers from La Perla, a poor neighborhood packed tight between the north wall and the ocean, to help rid it of graffiti, soot and fungus.

The part that crumbled in February, rousting a chagrined Mr. Chávez from his lunch and closing a lane of the street indefinitely, is being studied by the island's Department of Transportation. It will probably build an underground retaining wall before putting the stones back up, Mr. Chávez said. Witnesses reported several large trucks or school buses had passed in the minutes before the wall collapsed, he said. The park service wants trucks and buses banned from Calle Norzagaray, the only busy street that adjoins the wall, but José M. Suárez, executive director of the Puerto Rico Tourism Company, a government agency, said he was hesitant to support that. "The experts are saying if we don't do it, we might not have these walls forever," Mr. Suárez said. But he also said he represented tour buses that shuttle visitors to the wall from cruise ships and hotels, adding, "Right now I am standing still." Water traffic, too, is a threat. In 1999 a Russian oil tanker ran aground at the wall's northwest corner, damaging a breakwater. Cruise ships - Old San Juan's bread and butter - pass the wall as they enter the harbor, causing no obvious damage but moving some, like Mr. Chávez, to wonder how the wall would have held up if ships their size had attacked. When they glide past the wall, he said, "they're right on your level and it's a spectacular sight." It is perhaps the one pairing of old and new that he does not mind.

|

La Muralla, the soaring 16th-centurywall in Old San Juan,

La Muralla, the soaring 16th-centurywall in Old San Juan, Spanish colonists started building La Muralla in the late 1500's,

Spanish colonists started building La Muralla in the late 1500's,  The part that crumbled in February is being studied by the island's Department of Transportation. It will probably build an underground retaining wall before putting the stones back up.

The part that crumbled in February is being studied by the island's Department of Transportation. It will probably build an underground retaining wall before putting the stones back up. The wall also borders the La Perla neighborhood,

The wall also borders the La Perla neighborhood, Now Old San Juan, the pastel-and-cobblestone neighborhood

Now Old San Juan, the pastel-and-cobblestone neighborhood