|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. THE NEW YORK TIMES Bronx Haven Is Threatened, But Denizens Still Dream By ALAN FEUER September 26, 2003

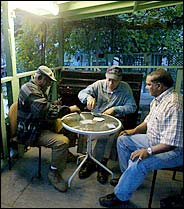

Playing rummy at the Rincon Criollo casita in the Bronx were, from left, John Vasquez, Charlie Torres and Robert Acevedo. Summer ends the same way every year at Rincon Criollo, a tiny wooden bungalow at Brook Avenue and 158th Street in the Bronx. Jose Soto eats an apple from the apple tree he planted 30 years ago. Louis Ramos tends his pepper and tomato gardens in a plot behind the shack. Felix Rivera hums along to island folk songs as Red the cat curls up beside the radio. Jose Rivera, no relation aside from friendship, slowly drinks a beer. Not much has changed for decades at Rincon Criollo, or the Down Home Corner, one of the oldest Puerto Rican-style casitas in New York. For years, the men here have welcomed autumn by fooling themselves with harmless fantasies that the summer ways and breezes will go on forever. For years, they have also fooled themselves by ignoring the fact that, sooner or later, their communal hangout will be gone. Nearly 13 years ago, city, state and federal agencies began to put up condominiums as part of the Melrose Commons development project, which now threatens the casita – the Spanish word for "little house." Five years ago, the city's Department of Housing Preservation and Development took control of the land to speed the plan along. Three years ago, a community group called We Stay/Nos Quedamos got an $8.2 million federal grant to continue the development by building houses for the poor and elderly of the neighborhood. And this year, like most, the efforts to displace Rincon Criollo have ground on. The end has not come yet, though it is near. "It's closer than it's ever been to getting done," said Yolanda Garcia, the executive director of We Stay/Nos Quedamos. If it seems somewhat strange that a community group like We Stay/Nos Quedamos wants to displace Rincon Criollo, which after all is a thriving part of the community, Ms. Garcia reluctantly agrees. Still, in her mind, building low-income housing in the Melrose section of the Bronx is more important than maintaining the gardens and traditions that have flourished at the casita for nearly 30 years. "We have to achieve a balance," Ms. Garcia said. "There are homeless people here. There are people tripling and quadrupling up, and they need housing. It's called change. And when the winds of change blow in, everybody trembles." Strangely enough, no one seems to be trembling all that much at Rincon Criollo. It is possible the men do not believe their cherished place will be destroyed, but it is just as possible that faced with its inevitable, if not imminent, destruction they simply do not wish to believe. Felix Rivera, a 68-year-old retired taxi driver, wandered the paths beneath the grape vines just last week. The dirt was dappled with spots of broken sunlight. The air smelled tartly of not-quite-ripe autumnal fruit. He spoke about the place in an unapologetic present tense that was nonetheless inflected with nostalgia. "This is my home," he said. "I come through the gate every day sick like a dog, but when I leave I feel like a brand-new guy. All my problems, I leave over there." With that, he gestured to the gardens. "I talk to God like in a paradise," he said. Mr. Ramos, 56 and recently retired from the United States Census Bureau, was bent above his pepper vines the other day, the unlit plug of a cheroot stuck firmly in his teeth. He was born in Puerto Rico, but left when he was 2. He, too, said he thought of the casita as his home. "Just looking at this place, I went through a transition," he explained. "Like a rebirth. It tapped my memory and brought back my parents in Puerto Rico. I never felt like I belonged in New York City – there weren't any palm trees, the people didn't speak my language. But when I came here, I didn't feel out of place." A sense of place: this is what Rincon Criollo seems to provide the 50 men or so who might drop in on any given day to work the gardens or sit on the wooden porch to catch the sun. The house, with its paneled shutters and open yard, reflects the architecture of the shanties that once dotted Puerto Rico's mountainsides and coasts. Inside, there might be artisans constructing panderetas, or Puerto Rican tambourines. Outside, others might be roasting suckling pigs and drinking slugs of native moonshine. Rincon Criollo is more than a place to relax with friends. It is half hangout, half cultural center, and has long served as the city's unofficial center for the bomba and the plena – Puerto Rico's traditional percussive music styles. Under a plan proposed by Ms. Garcia, the casita would be moved to a new plot across Brook Avenue, a block away. While the men who use Rincon Criollo say they sympathize with the need for housing, they say it is hard to move a garden. "What do we do with the apple tree?" Mr. Ramos asked. "It's been there 30 years. Songs and poems have been written about that tree." He and the others at Rincon Criollo have placed their faith in a city statute that requires, before development, a case-by-case review of all gardens on city land, especially ones that can be said to anchor their communities. They have also looked for help toward a lawsuit that was filed in 1999 by Eliot Spitzer, the state attorney general, and settled last year. The suit, which blocked the sale or destruction of hundreds of the city's community gardens, argued that gardens in existence for 20 or 30 years deserved the same protection as the city's public parks. Mr. Soto, the founder of Rincon Criollo, said that if any garden merited protection it was his. After all, he said, before he built the place, the lot it sat on was a junkyard filled with busted bicycles, rusted cars and men of dubious repute. Plans to demolish the garden, however, have been approved by city housing agencies, the local community board, the Bronx borough president's office and the City Planning Commission. Construction is scheduled to start next year. "We are confident that you will agree with other representatives of the community that the creation of new residential and commercial space will benefit all of the families in the Melrose neighborhood," Carol Abrams, a spokeswoman for the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, said in a written statement. Jose Rivera said something different as he stood beneath the grape vines a few weeks ago. "This place is going to be knocked down," he said. "Next year? Probably not. In two years . . . " Now he could only shrug.

|

__________

__________