|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. THE NEW YORK TIMES Releasing Album, Williams Makes His Dream Real By JACK CURRY July 13, 2003

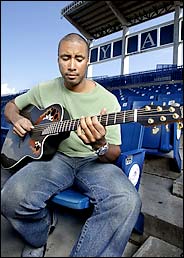

Bernie Williams in Tampa, Fla., in February. Williams fell in love with his father's strumming and dedicated a song to him. Bernie Williams was only 5 or 6 years old when he first started dancing around the living room to the gentle strumming of a guitar in his home in Vega Alta, P.R. His father, Bernabe Williams Sr., had brought the guitar back from Spain, and the soft, soothing sounds provided entertainment for the family and enlightenment for a little boy. Seeing his father play the guitar, hearing the music it created and studying the impact it had on people were all appealing to Bernie. He moved his feet because that is what children do in those playful settings, but soon he was dancing to get closer to the music. He wanted to feel it and understand it. And, eventually, he did. "I remember just being attracted to the music," Williams said. "When I had the opportunity to pick up a guitar, it was like it was inside of me. It was a challenge to learn how to play it. I didn't want to stop." He never has. Even as Williams showed tremendous promise as a young baseball player, he always apportioned time for music and always figured he was much more likely to be a guitarist in a club in Manhattan than a center fielder at a ballpark in the Bronx. Williams scampered to music lessons with his guitar faster than he ever scooted to baseball practice with his glove. Even after Williams developed into an All-Star with the Yankees and an instrumental player on four of their World Series championship teams, he kept an amplifier beside his locker, traveled with a guitar strapped to his back and picked at the strings in the clubhouse. Music never vanished from his hectic world, always following him and relaxing him. "It's a side of me," Williams said, "I've always had." The two disparate sides of Bernie Williams will mesh today when he plays for the Yankees in Toronto, gets on a chartered plane after the game and flies to Chicago to play a show at the House of Blues tonight. Williams will be promoting "The Journey Within," his debut recording, which includes seven original songs among its 11 tracks and will be released by GRP Records on Tuesday to coincide with the All-Star Game. Williams conceded that he will be nervous for the 45-minute set, the only concert scheduled to promote the album because he has another full-time gig at a pretty decent salary of $12.5 million a year. There will be an all-star band supporting Williams, whose mother, Rufina, and younger brother, Hiram, are traveling from Puerto Rico and whose wife, Waleska, and three children will also be there. "One thing I've got going for me is I'm a baseball player playing a guitar," Williams said. "I'm not a renowned jazz guitarist. There should be people who are just happy to see me up there playing." Williams is being modest. He is a skilled musician who attended a music high school on scholarship and has been playing guitar for 26 years. Loren Harriet, who produced the album, said Williams coolly combined technique and emotion, two critical traits, to make him an "amazing guitarist." Harriet has worked with Paul McCartney, who, he said, listened to "The Journey Within" and remarked, "I love this record." Williams almost swallowed his cellphone when he heard that McCartney adored his Latin-flavored jazz with a tinge of soul. Rubén Blades, the Grammy Award-winning singer who was chiefly responsible for helping internationalize salsa music, sings on the album. Blades knew Williams as the center fielder for the Yankees when he first arrived at Globe Studios in New York in January, even though he had seen Williams briefly jam with Paul Simon several years ago. "I imagine everyone who went in there thought we'd be helping good old Bernie fulfill his fantasy," Blades said. "We got in there and he was really, really good. I was pleasantly surprised." When Blades was asked how long it took him to recognize Williams's talent, he said: "The first song. I've played with everyone. Salsa, jazz, rock. I've played with a lot of people and listened to a lot of music for over 30 years. You recognize quality immediately." Often aloof and usually subdued, Williams showed a rare giddy side when a reporter told him about interviewing Blades. "What did he say?" Williams screeched. "Tell me what he said. He's my hero, man." Williams's hero saw a 34-year-old performer with exquisite taste. Blades praised Williams for the quality of his arrangements, the beauty of his melodies and structures, the cleanness of his playing on an acoustic steel string guitar and the imagination in his songs. He expected a baseball player who dabbled as a musician and discovered a music comrade. "What he has done is like jumping in a pool and, on the way down, he's trying to find out if there's any water in it," Blades said. "I think there's a lot of water in there for Bernie." Interestingly, Williams does not consider recording music on such a grand scale as a career after baseball. He will always play the guitar, but the experience, as exciting as it has been, was an intense month of recording, so Williams might not commit to another project anytime soon. "I have no idea what I'm going to do after I finish playing baseball," Williams said. "I do know, in some way, it's going to be related to music. It's been too big a part of my life. As far as a career in music, I don't know if I'll go that route." Williams explained how being a musician who records and tours might be more grueling than being a professional athlete, and he is not interested in continuing that after retiring. The more than $100 million Williams will end up earning in his career makes any subsequent choice easier. Baseball has given Williams a platform, he said, and it allows him to pursue music vigorously or "chill and just play for fun." As a teenager, Williams woke up at 5 a.m. so his father could drive him to his high school, Escuela Libre de Música in San Juan, and he usually did not return home until 8:30 p.m. because of athletic events. It was a grueling schedule, but two decades later, Williams spoke appreciatively about his good fortune of playing music and baseball simultaneously as a youngster. "The Journey Within" includes songs about Williams's father, his wife and his son, Bernie, and other tunes Williams called "the fun songs." The most emotional song is "Para Don Berna," the tribute to his father, who died two years ago. Harriet compared it to Eric Clapton's "Tears in Heaven." Hiram plays cello on it. "I told my brother I hoped I'd get to play it for my father," Williams said. "The song helped in my grieving process. It didn't put closure on my relationship with my father. It put closure on my grieving." Williams has never been too chatty, and he said playing music allowed him to "express the feelings I might not have the opportunity to say or might not be able to say." When Williams writes a song, plays it on his guitar and can tell that people understand it, he says it is exhilarating. It is like being 5 or 6 again, dancing around the living room.

|

Lou Rocco/New York Yankees

Lou Rocco/New York Yankees